Literature can help us confront the most difficult truths: My Research Journey

Joanne Touhey-Francis, 23/09/2025

When people ask me what I do, I often hesitate before answering. To say “I’m a researcher in Literary Practice” doesn’t always capture the heart of it. What I really do is write stories, wrestle with memory, and dig into the silences that shape families and identities. I didn’t set out to be a researcher. After my bachelor’s in social care, I didn’t really know what I wanted to do next. One afternoon, driving in the car, the radio advertised the RTE Short Story Competition.

I didn’t call myself a writer at the time. The most I did was write in my diary or scribble the occasional story that I almost immediately scrapped. This was the first time I’d ever heard of a writing competition, and two thousand words seemed impossible. But I had just finished The Silent Patient, and was inspired to try something in that genre. So, I wrote about a woman who had suffered a head injury in a car accident, resulting in her husband’s death, yet in the hospital, he was by her bedside. By the end of the story, the reader was left uncertain whether she was trapped in a hallucination or if he had ever died at all. It wasn’t my best work. It sounded much better in my head than it did on paper, but I submitted anyway. That feeling, of creating something and having someone else read it, was addictive. I wanted to do it again. I joined a six-week creative writing course and shared the story I wrote for the competition. That was my first real taste of feedback and editing. Who knew you weren’t meant to submit your first draft? Or that you should let your story sit and return to it later with a fresh pair of eyes? Or, even most importantly, proofread?

The group said it had potential, but I was mortified. I wanted to take it back, both from them and the competition. Even now, I can’t open that story. There’s a saying that a writer must write for 10,000 hours before they truly find their voice, and that there will be many bad stories in you first before you create something worth keeping. That was certainly one of mine. (Of course, some writers get lucky on the first go.) When the course ended, I missed it. I missed writing with prompts, sharing with others, and having a reason to sit down each week. So, I looked online for how to become a writer. I bought a book on Amazon with tips on getting started, and somewhere in the middle of falling down an endless rabbit hole of scrolling, I came across a master’s in writing. I hadn’t even realised such a thing existed.

The master’s was at the National University of Galway (now Galway University). I thought if I ever did a master’s, it would be in social work, but I told myself if I weren’t accepted into writing, I’d apply for social work the next year. For the application, I needed to send a writing sample of two thousand words. The only piece I had was Wounds, my thriller. I rewrote it with alternative endings, took on the feedback from my writing group, and sent it off. I was accepted just as COVID hit, which worked in my favour since commuting would have been difficult with two young kids. Around that time, I had just read Charlotte Perkins’ The Yellow Wallpaper, already loved that genre, and had long counted Jane Eyre as my favourite novel. I planned a three-part short story called Rosenfield House, about a woman suffering from depression after multiple miscarriages, set in the 1960s in Windermere. Her husband, a psychiatrist, seemed controlling, though through the narrator’s eyes, he was protective and caring. He prescribed her medication for her mental health and took her to his old family home, where they stayed with his childhood governess, a figure who seemed unsettling from the start. What I didn’t realise at the time was that the themes I kept circling in fiction—control, silence, power, and the blurred lines between care and harm—were the very ones waiting for me in nonfiction. When it came to writing from life, I felt I was lost, but slowly I began to see that the same questions I explored through imagined characters were rooted in my own lived experience. What am I going to write? Nobody likes to write about themselves, surely. I certainly didn’t. I thought I had nothing to say. We started off with small prompts, such as “What’s your favourite photograph?” “What does home mean to you?” Then came a critical piece about someone, anyone. The only person I could think of was my dad. Strangely, a new voice came through, and I wrote about him in the second person. It turned into a comical piece about his self-centredness, and without overthinking, I sent it in. To my surprise, the class loved it.

A few weeks later, I wrote about my mam. Her gambling, the financial abuse I suffered at her and my granny’s hands. Then, about my stepdad. His alcoholism, his psychological abuse. As the words poured out, I cried. Buried emotions resurfaced. I was told I had a story worth telling, but I didn’t believe it. Not straight away. I thought everyone had a story like mine. To me, the life I grew up with felt normal.

When I finished my master’s, a friend told me she was applying for a PhD in Literary Practice. I hadn’t planned on researching; it was never in my cards. But I was curious. She explained that it combined a creative project with a critical essay. She was writing a memoir that made up 80% of her thesis, with a 20% critical component. I thought, I’ve made it this far, never having written an essay, how could I possibly write one at a doctoral level? And could I really write 80,000 words about my life, when I had struggled with 30,000 for the master’s? But I applied anyway, suggesting a memoir, half-convinced they would turn me down. It was tough writing, especially about my own life, that I realised research could be survival, a way of making sense of the past while contributing something meaningful to the present. So, when I was accepted, I was delighted.

My memoir traces my childhood and adolescence, marked by dysfunction, secrecy, and abuse, but also resilience and a belief in the power of words. Alongside it, my critical essay examines how memoirists like Jeanette Walls, Tara Westover, Katriona O’Sullivan, and Maya Angelou represent violence, silence, and survival. Writing in this space means constantly moving between both the storyteller and the analyst, allowing each mode to illuminate the other. It has been both challenging and transformative. Some days it feels like reopening old wounds, and others like lifting a weight I have carried for years. I often think of it as pulling back a curtain, revealing what has long been hidden, not only for myself but for others who might recognise something of their own story in it.

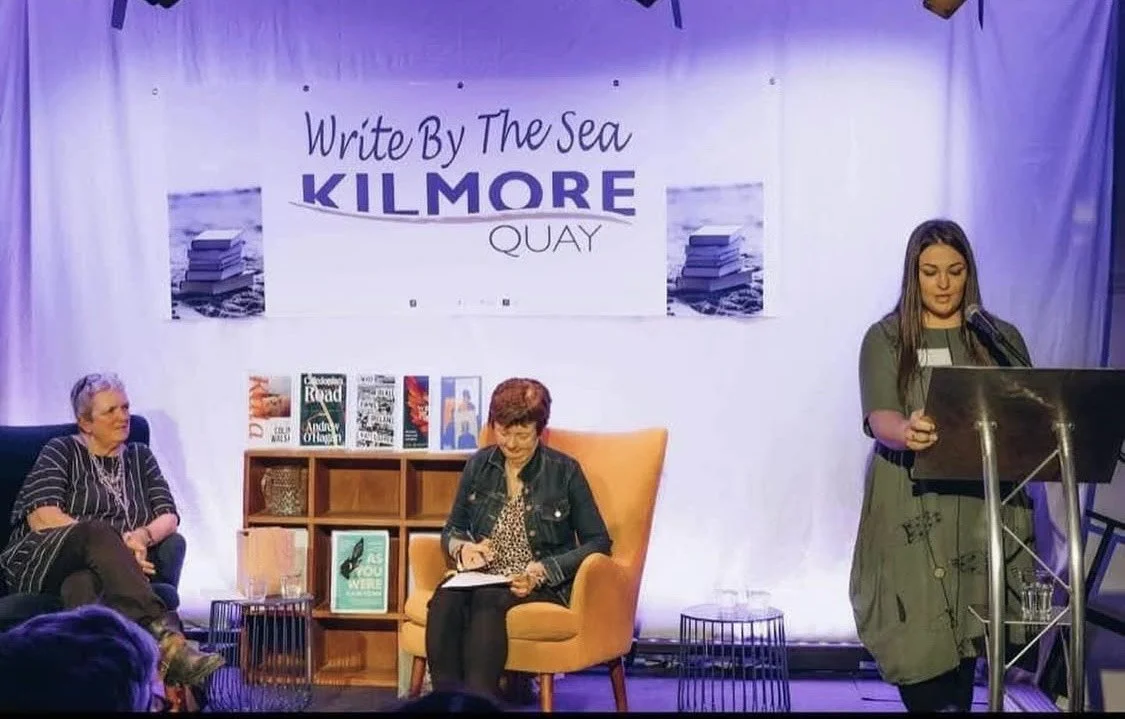

One of the most surprising lessons has been realising that research is not just about finding answers, but also about asking better questions. How do we represent trauma without sensationalising it? How do we give voice to the unspoken while respecting the complexity of memory? What responsibility do memoirists have to the people in their stories? These are not questions with simple solutions, but they shape how I approach both my creative and critical work. This journey has already taken me to unexpected places. In 2024, an excerpt from my memoir won the Write by the Sea competition, and I had the opportunity to read it at the festival. Sharing such a personal piece, in front of an audience, including people close to me who had never heard it before, was both terrifying and liberating. It reminded me that research doesn’t have to stay confined to the academy; it can reach and resonate with wider communities.

Looking back, I can see how each step, from sitting at home with my husband and kids to standing on a festival stage, led me here. Research, for me, is not just about producing a thesis. It is about finding a voice after years of silence and showing how literature can help us confront even the most difficult truths. Behind every research project is a person, a path, and often a personal reason for choosing that work. I hope that by writing about resilience, silence, and the power of memory, I can contribute to a broader conversation about how research can not only change how we think but also how we live.

Research is not only about producing knowledge, but about breaking silences—my own, and, I hope, others’ too.

Joanne Touhey-Francis

Joanne Touhey-Francis is in the final year of her Ph.D. in English at Trinity College Dublin and is writing a memoir as part of her research. One of her chapters won 1st place in the Write by the Sea Memoir Competition 2024.

Joanne is also pursuing a Master’s in Library and Information Management at Ulster University and gaining hands-on experience as a Library Intern at TUS Midlands. She holds a degree in Social Care Practice from Athlone Institute of Technology and a Master’s in Creative Writing from Galway University. Joanne’s work has been published in journals such as The Stinging Fly, Tír na nÓg, The Waxed Lemon and Olney Magazine.